by Louis O. Kelso and Patricia Hetter Kelso

At the annual shareholders’ meeting last May, General Motors’ Chairman Roger B. Smith said that not even great technology and the magic of robots can overcome the competitive disadvantage of high American labor costs: at GM hourly workers earn $8.00 an hour more than their Japanese counterparts. Smith suggested that perhaps some wages or benefits be replaced with a “profit sharing plan.” Ford Motor Company Chairman Phillip Caldwell recommended the same to Ford employees.

This poses a provocative question: Is any form of profit sharing a suitable trade-off for wage reductions from the standpoint of the employees, the company, or the union? Is there some alternative that would better serve the interests of all parties in restoring the American automobile industry’s worldwide manufacturing preeminence?

We think there is. If a Kelso ESOP1 is used as a trade-off for a wage cut, the dollars invested by GM in its industrialization will go at least three times as far, to the economic benefit of the company, GM employees, and the public.

Let’s first acknowledge that a mere deferral of pay following the example of Chrysler, which continues to post record losses, will not make Detroit competitive with Japan. It is elementary that neither GM nor Ford can become competitive by postponing costs. Winning requires cost reduction.

Suppose GM did establish a qualified profit sharing plan with a variable contribution formula. If profits do not rise, the contribution would be nominal in relation to employees’ pay reductions. Alternatively, the larger the profits, the larger the contributions to the plan.

If the GM-UAW negotiations took that route, let us suppose that as a trade-off for a $1 billion annual wage reduction for five years, out of an annual payroll of nearly $18 billion, GM agrees to contribute twice that amount annually to the profit sharing plan. The plan would then invest these funds in a diversified portfolio of carefully selected presently outstanding securities. But in doing this, General Motors is merely investing, on behalf of GM employees, in the outstanding securities of other corporations. This investment is only marginally profitable (six percent or about half the rate of inflation). Nor is there anything the employees of GM can do in their role of workers or managers to affect the profit performance of a company whose secondhand securities are held in the profit sharing plan. Nor can GM employees influence the mood swings of the general stock market. Employees can only affect the profitability of the company they themselves work for — in this case, GM.

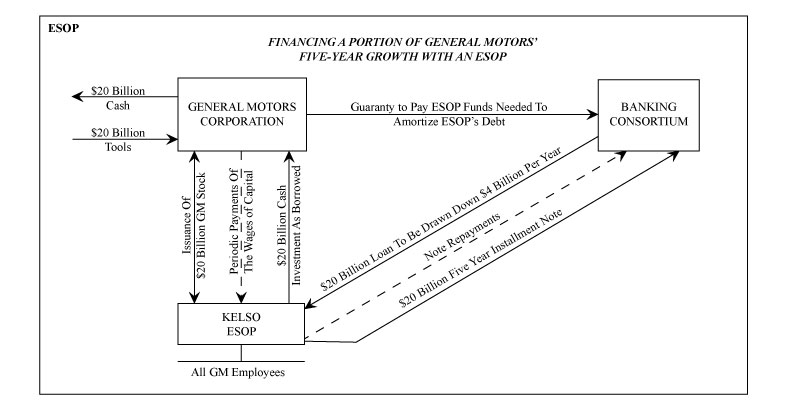

Now let us consider an alternative scenario. Suppose, in response to Chairman Smith’s request, GM and the UAW agreed that all GM employees — non-union as well as union, salaried as well as hourly — would take pro-rata an aggregate $1 billion per year wage reduction and not ask for an increase until GM is again the world’s most profitable automobile manufacturer. In return for this critical concession GM and the UAW would agree to replan their financial future with a Kelso ESOP. Let us further assume that GM’s estimated capital budget for the next five years is $40 billion,2 and that a banking consortium agrees to lend the ESOP $20 billion (half the five-year projected capital budget) at an interest rate that would fluctuate with prime. GM would guarantee the loan. The loan agreement would further provide for the loan to be repaid over five years in annual increments of $4 billion. The ESOP would give its note or notes to the lenders. It should be remembered that repayments of this loan, both principal and interest, are deductible from corporate income taxes. Assuming that GM, for combined state and federal purposes, is in a 50 percent tax bracket, the ESOP financing plan is twice as efficient as conventional finance in retiring the debt principal. The ESOP would invest the borrowed funds, as received, in equal amounts of newly-issued GM stock at market value or at appraised value if the stock is of a class not in the market.

The ESOP’s allocation formula or financial plan for GM employees would provide that as periodic repayments on the loan are made by GM through the ESOP to the lenders, a block of the previously purchased GM stock, corresponding in value to the amount of the repayment, would be allocated among employees in proportion to their relative compensation. Employees would have no personal liability on the ESOP’s note. If it could be shown that the stock sale would cause material dilution of existing GM shareholders, a class of preferred stock not designed for public trading, convertible and redeemable in common stock, suitably priced, could be used for the purpose.

However, the idea of “dilution” would have to be carefully examined. Dilution is of two kinds: political and economic. Political dilution occurs where voting control is shifted to a new power center. Economic dilution occurs where an event causes a reduction in true earnings per share. Neither kind of dilution would take place with a Kelso ESOP; economic dilution cannot occur unless it exceeds asset enrichment. Asset enrichment occurs when new stock is sold at full value to the ESOP in such way that each dollar of proceeds has the financing efficiency of three or more dollars of corporate income used conventionally to finance growth.3

Possible dilution must also be offset against the wage-containment tendencies and employee motivational power of the ESOP.

As the GM-UAW Kelso ESOP draws down on the loan from time to time to buy newly-issued GM stock, GM would use the proceeds of the stock sale to “reindustrialize” itself.

How the ESOP Trebles Financial Efficiency of the Corporate Dollar

Every corporate investment that meets the test of proper financial planning is actually two transactions in one. The corporation acquires new productive assets. At the same time, stockholders’ equity is increased. This is true because the corporation is a juristic person, but not a real person. In reality, the corporation is a financial planning device that connects people with capital assets and with other people in specifically planned ways. In economic reality, only human beings count; there are people who produce through their labor, people who produce through their capital, and consumers. Every producer is a consumer, and every consumer should be a producer, although in a badly planned economy there are unfortunately also parasites that consume but do not produce, although they may appear to do so.

When a pension or profit sharing plan invests in spent (i.e., already outstanding) stocks, the employees get a beneficial interest in those spent stocks. In terms of productive capital assets, the employer gets nothing. This is not two financing transactions in one; it is simply inept planning. The yield of the spent stocks will be about six percent, perhaps half of current inflation. The purchasing power of those stocks for purposes of the employees’ retirement security begins to shrink on purchase.

When an ESOP is used to plan corporate growth, its effect must be compared with the dominant method used today — financing from cash flow, which accounts for 95 percent of all new capital formation in U.S. corporations.

Thus ESOP financing cannot be compared with investing in pensions and profit sharing plans because these are not financial planning tools at all; they finance nothing. They buy spent stocks.

In addition, GM and GM’s employees would each save approximately $300 million in Social Security taxes that would have been collected if the $5 billion in wages had not been ceded. The total $600 million saved could, to the extent agreed upon in collective bargaining, be converted by the ESOP financial plan into employee-owned GM stock.

Conservatively estimating that GM employees would on average be subject to the 25 percent personal income tax rate, the employees would save $250 million per year, or $1.25 billion over five years, in personal income taxes.4 The ESOP, again to the extent agreed upon in collective bargaining, would convert that savings into employee investment in GM stock.

A $20 billion employee purchase of GM stock would create an average employee portfolio, at cost, for each of GM’s 517,000 employees, of $38,684. If the financing plan were renewed, this amount could grow to $77,369 in ten years and to $166,152 in fifteen years. The employee-investors, however, would not be passive investors, but stockholders in a position to make their investment, along with that of all other GM stockholders, grow in market value over a sustained period. The value of the stock should appreciate substantially during the five-year period and thereafter as GM regains its economic health through lower cost products and happier, more secure, and more highly motivated employees.

GM employees would also acquire a second source of income. Kelso ESOPs normally pass dividends through the trust currently on already amortized shares. The trust can be planned to make dividends to the employee-stockholders payable in pre-tax dollars — double the financing efficiency of conventional dividends.

Greater Retirement Security at Lower Cost

The UAW and GM should launch an extensive study of the desirability of achieving yet another major cost savings through a Kelso ESOP. Fixed benefit pension plans now cost GM nearly $2 billion per year. But GM’s employee retirement pensions, like pensions from any retirement funds invested in secondhand securities, are in most cases grossly inadequate. Their use is the essence of bad financial planning. No employee investments in secondhand securities, sluiced back and forth day after day in the marketplace to support the investment community, can compare with a direct investment in General Motors. Pensions connect employees with a low-yielding retail investment — perhaps six percent per year or about half the current rate of inflation. A Kelso ESOP financial plan connects employees with the 20 to 30 percent average pre-tax return on capital in GM. This is the range of pre-tax earnings in most major U.S. corporations.

One of the principal reasons U.S. industries have become uncompetitive as a result of cost inflation is the growing tendency of both management and labor to seek retirement security through qualified pension and profit sharing plans. Through these devices brokers sell American workers the worst “investment bargain” conceivable: already outstanding securities. This is financial planning gone mad. Kelso ESOPs make credit available to employees to buy newly-issued equity stock on terms where part of the pre-tax yield of the assets represented by that stock pays for it.5 At the same time, as we have seen, it finances the employer corporation’s capital requirements in a way that gets three dollars’ or more use out of every dollar of capital cost when compared to conventional internal cash flow financing, the source of financing for 95 percent of all U.S. corporate growth!

Secondhand securities purchased by pension and profit sharing trusts can never pay for themselves. This is why retirement provisions in American enterprise are uniformly inadequate and rampantly inflationary. An ESOP financial plan should be used instead. Diversification can be effected after the ESOP has accomplished its three-fold task of growth financing for the employer, estate-building for the employees, and tax saving for both the employer corporation and its public shareholders. The financial community’s talents could be better used to diversify in this way without crippling business with bad financial planning, irrecoverable costs, and barren investments.

Of course, the U.S. Internal Revenue Code should be amended to clarify the right of ESOPs to be diversified by exchanging in the securities markets, if deemed desirable, some of the securities of the sponsor-corporation for other appropriate investments. Senator Russell Long, the distinguished former chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and now its ranking minority member, who first introduced ESOP financial planning to Congress in 1973, has an answer for this kind of problem. “If the law needs changing so that it will make sense, you’ve come to the right place. That is what we do here in Congress.”

Non-Quantifiable Advantages of Kelso ESOP Financial Planning Both to GM and Its Employees

The UAW and GM, through collective bargaining, would divide the measurable economic advantage of ESOP financing between GM, its public stockholders, its customers, and its employees. The UAW can at last champion the constitutional rights of its members to access to capital credit —the ability to buy capital and pay for it out of what that capital produces, thus raising employees’ incomes without raising the employer’s labor costs. This is the financial planning tool foreign competitors hoped we would never discover; the tool we had better learn to use before they exploit it first.

With the establishment of a second source of current income for GM employees — dividends — the necessity for demanding progressively more pay for the same or diminished work input is greatly reduced. As Kelso ESOP financial planning becomes general in the economy, we will reach the maximum levels of employment achievable. The U.S. economy is replete with unsatisfied needs and wants for physical goods and services. What we need now is consumers with incomes from non-inflationary sources6 to make potential consumer demand effective. This means that what consumers cannot buy out of their labor incomes they must be able to buy out of their capital-produced incomes. We may well then achieve true full employment for a decade or two. The unemployment that will eventually follow in the wake of technological advance would be different in kind. Superseded employees, secure in their capital incomes, could afford to enjoy their leisure. Unemployment is not so bad when you can afford it.

We should all be aware by now that technological change makes capital, not labor, more productive, and that the euphemism “rising productivity of labor” is simply a way of shifting to consumers the costs of paying for the increasing needs of workers. Unfortunately, solving labor’s income distribution problems in that way forces consumers to pay higher prices for the same or even lower quality goods and fewer services. The name of this phenomenon is “inflation.” Since employees are also consumers, and the same technologically-initiated forces are at work throughout the economy, the dependence of employees upon their decreasingly productive labor rather than upon increasingly productive capital assures perpetual inflation. Kelso ESOP financial planning eliminates this hopeless spiral at its source.

The lesson of foreign competition is that much of our labor is overpriced. At the same time, we know that only a tiny fraction of the wages of capital are paid to capital owners — the stockholders. After all, state and federal governments, in a vain attempt to compensate for bad financial planning which long ago failed to guide the economy into broader capital ownership, take more than half of capital-produced income, particularly if the corporate portion of Social Security taxes is included. In order to finance growth, boards of directors then divert about three-fourths of the remainder of capital-produced income away from stockholders and back into financing the corporation. Clearly, a higher payout to stockholders of the wages of capital, broader ownership of capital, and more efficient methods of planning and financing economic growth — all elements of sound financial planning — are what is required to beat foreign competitors, reduce inflation, and meet our ultimate economic need: higher capital-produced incomes for all consumers except those who are already rich.

Advantages to GM and GM Employees

- General Motors would acquire, at negligible issuance costs, a new body of employee-stockholders equal in number to half of its present public stockholder base. This would be an enormous step toward the unification of the interests of management (who would be participants in the Kelso ESOP), employees, public stockholders, and consumers.

- Employees would be powerfully motivated to make GM (“their company”) succeed in international and domestic competition.

- For GM employees, the ESOP would offer an additional market for their stock at the time they wish to sell it.

- Employees would gain a significant voice in GM affairs at stockholder meetings. There could be no more interested or knowledgeable stockholders, nor stockholders that could contribute more to the performance of GM than its own employees.

Advantages for the United Auto Workers International Union

- The union could expand its sphere of service from interest only in wages, hours, and working conditions to interest in sound financial planning and the acquisition of capital ownership for all its members. It is capital ownership that removes the cause of poverty. It is capital ownership that is the chief source of leisure, affluence, and freedom from toil, and ultimately the only way for employees to acquire sufficient capital-produced income to provide secure retirement.

- The union would acquire the most powerful recruiting tool in the history of the union movement: the power to assist members in planning a sound economic future through a combination of labor and capital earnings. White collar employees have always been reluctant to demand more pay for the same work. Employee resistance to unionism will change to interest in and reliance upon it. After all, the problems of employee stockholders differ in many ways from those of public, non-employee stockholders.

- The UAW would take an interest in financial planning and would exert an influence on the design of the GM-UAW Kelso ESOP towards ends deemed reasonable and advantageous to the employees, to GM, its stockholders, and its consumers.

- The UAW would seek the services of financial planners for its members as stockholders in GM, and would enlarge its consulting staff appropriately. It would participate in negotiations as to what part of the economic growth of GM should be financed in such a way that UAW members would become the owners of the stock representing that growth, and the extent to which the wages of capital would be paid currently to stockholders.

- Finally, the UAW could become the spearhead for obtaining equal protection for its members of their constitutional rights to credit finance their capital acquisition in the process of providing General Motors — and other employers for whom its members work — highly efficient, low-cost capital to power their growth and competitiveness.

What sound financial planning can do for GM, it can accomplish for enterprises and individuals throughout the economy. The other financial planning tools referred to in a footnote above are constructed on the logic of the ESOP.

FOOTNOTES

1 The Kelso ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan) is a financial planning device intended to advance the mutual economic interests of the employees, the employer, and the public. There are many ESOPs that are not Kelso ESOPs.

2 “How General Motors Stays Ahead,” Fortune, March 19, 1981, p. 49. GM’s ten-year capital investment plan is estimated at “an almost inconceivable sum — approaching $80 billion . . . .”

3 The three-to-one advantage of ESOP financial planning in this case consists of: $20 billion of equity opportunity — the opportunity to prudently use equity when without the ESOP General Motors would not issue common stock to finance growth; $20 billion of tax savings from repaying the loan principal in pre-tax dollars, and $20 billion of capital ownership generated in GM employees in the five year period, a result just as important to sound financial planning as new capital formation for GM.

4 Upon taking their stock out of the trust on retirement or otherwise, employees would be subject to a much lower capital gains tax.

5 The Kelso ESOP is but one of eight financing tools designed not only to fulfill every variety of capital financing need, but also to build viable capital estates into every type of consumer, whether a corporate employee, a government employee, a retired person, a technologically superseded worker, teachers, artists, or the disabled. At the very moment in history when Americans are beginning to have second thoughts about the soundness of conventional financial planning that only makes the rich richer while denying equal protection of credit laws to those who want to own capital but cannot, these financial planning tools promise to fill the void in the constitutional rights of the 95 percent of citizens who have been economically discriminated against.

6 Namely, incomes not dependent either upon taxation-dependent boondoggle or welfare, both of which are inflationary.

— Originally published in THE FINANCIAL PLANNER, Vol. 10, No. 11, November 1981

▪ Related Article – Yes, an ESOP Can Still Save General Motors by John Menke